'You Can Live the Wrong Life'

What is 'success' as an artist? What is the right or wrong life? Thoughts on 'Perfect Days', Rachel Cusk, Picasso.

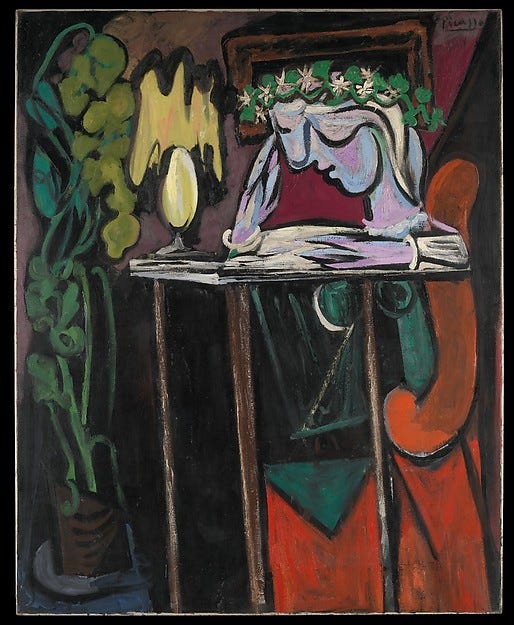

There’s a game I sometimes play at the museum: ‘what kind of painting am I today?’ Never, despite my best attempts, am I an angelic Botticelli. When hungover and weary, perhaps a Toulouse-Lautrec. When swaddled in loneliness, absolutely an Edward Hopper. Recently, though, I’ve been drawn to the Picassos. The sharp edges, the straight lines, and the slight sense that something is off. His figures never seem to be in precisely the right place. It is like they are in the wrong place, the wrong form, the wrong life. There are some paintings of his that resist that viewpoint. One of them is in the Met in New York. The painting is called Reading at a Table, and it is about exactly that: a woman sitting alone at a table, reading a book by lamplight. Her body seems to morph with the chair, and the book is positioned in a way that it seems to flow into her body, becoming part of her. She has the flowy, strange style of Picasso’s characters, but the strangeness isn’t the first thing a person’s drawn to; it’s the serenity, the peacefulness. She is deep in concentration, smiling, but exclusively to herself. She is content, and precisely where she’s meant to be. Living a good life. Living the life that is right for her.

⁂

That idea of the ‘right life’, and the ‘wrong life’, has been haunting me in August. It started with an interview that the novelist Rachel Cusk gave several years ago. She was asked about talent, specifically creative talent, and how and why it is that people can’t or refuse to meet their potential. “You can live the wrong life,” she replied. She spoke about how time is, for so many of us, not really our own. Between work, caretaking, and the banalities of regular existence, it can feel like there’s no time left for the creative pursuits or hobbies that fill a life with meaning. The characters in her novel, especially Transit, are petrified by the sense that they are living the wrong life. Even the characters that are ‘successful’ are gnawed at by the suspicion that something is off, especially the narrator Faye, who is a published writer and steady teacher, who is on the surface living her right life. But still, there’s this prevailing sense of quiet desperation in Faye’s life. Her relationships are strained, her house is falling apart, and in the basement demonic neighbors screech and yell and disrupt all of her moments of domestic bliss. Even in the narrative of her own life, Faye is barely more than an outline of a person. She is the writer, the supposed wrangler of words and grand narratives, but she can barely corral the story of herself.

It's alluring to think of the ‘wrong life’ as something that is comically worse than the good things we love. In this way of thinking, my wrong life would be something like; working as an American border agent, building bonfires out of books, or cheering for the New York Yankees. But the wrong life strikes me as a thing of degrees, where you can be living some form of the wrong life while also doing things that are clearly part of the good life. That’s what I’ve begun to see in myself; a prevailing funny feeling that I’m not living in the right way, even though I am doing many of the things that ought to bring me joy.

The conditions of my wellbeing are frustratingly simple: as long as I am seriously reading and writing, I am content. Doing these things doesn’t solve all my problems, but working with words makes me believe that I can. Writing is a vessel that I pour parts of myself into. Without the vessel, I spill everywhere. I’m useless when I’m in that state: sloshing around, a sad little puddle that is unable to grab onto anything.

On my computer, there’s a spreadsheet that roughly tracks the number of words that I write each day. One of the tabs has pretty charts and graphs that update automatically. When the numbers go up: satisfaction, accomplishment. When the numbers go down: dissatisfaction, dread. The last few months have seen the numbers go up. Projects have been filed, things are being read and re-read, the work seems to be going vaguely in the right direction. I should be happy, or at least satisfied! But I am not! The only thing that has defined this period is a vague, indiscriminate ennui that pervades everything. It’s like I’ve been pouring myself into a vessel that’s too small. Or the vessel has cracks, and each time I pour I only slip right back out. Here I am, a puddle, smiling up at the sky. I am not unhappy, but also not where I am meant to be.

⁂ :)

In the backyard outside my bedroom are all sorts of trees: mulberry, peach. They’ve grown so much this summer that they’re nearly taller than the apartment building. Since I face east, the bedroom gets the sunrise, and this summer the orb has started rising behind a wide crown of trees. It casts yellow and orange shadows on my white walls. The shadows are the shapes of twigs and leaves. The scene reminds me of the movie Perfect Days, about a man named Hirayama who lives alone in Tokyo. His life is punctuated by strict routine. He drinks the same can of vending machine coffee each morning. Listens to a rotation of cassettes as he drives to his job as a toilet cleaner. He eats at the same restaurant, orders the same dish. But when he’s not working, he sits in a park and delicately saves a tree sapling in a pot made of newspaper, and aims his camera at the crown of the trees and takes a photograph. In his home Hirayama has a room full of saplings in different stages of growth, and we later see a box full of hundreds of photographs of trees, parks, and the shadows that foliage makes in the sunlight. And then there are thousands of photographs. In the quiet spaces of regular life, Hirayama has crafted an archive of his life’s work. He has done it because it’s beautiful, and gives him joy.

The movie is a love letter to creative expression and art-making, but it’s also tinged with sadness. Hirayama’s life is austere, solitary. He amasses this life’s work of beautiful art without nearly anyone knowing about it. It’s possible that not a single person will ever see it. It is like he has thrown his hands up and admitted that success is the wrong thing for him to chase, and so he goes about cleaning toilets, and living his life. We get the sense that somehow this is his right life, even if so many of the aspects of it are the complete opposite of what we are taught to crave.

Success is such a tricky, impossible word. All of the measures that we have of it seem to be external, and quantifiable: wealth, viewership, followings, square footage of the places we rent or buy. It is all the buzzwords: America, Capitalism, but it’s probably simpler than that. People want things that signal to themselves and others that they are not failing to live a good life. I’m immune to many of these quantifiable things generally, but it gets harder to ignore the yearning for success when it dovetails with the things that I truly love.

There was a picture that I used to post on Instagram, for instance. It was of me reading a book that was propped in my lap, or placed on a table, or held in just a way so that a large bookshelf was featured in the background. These kinds of curated images of perfect-little-lives still pop up everywhere, and they’re mostly silly. But they’re also sad. Reading flattened from a verb into a coat that a person can wear. A good and joyful life turned into a product. Even if I was barely making rent at the time, or miserable in every conceivable way, I could point to the images of Chaucer and Dante and Simone de Beauvoir and feel protection. As long as I had the mirage of living the right life, I was not completely living the wrong life.

The world has fortunately been liberated from my Instagram, but my brain hasn’t. I get lost in cravings for these familiar markers of public success. I’ve found new internet platforms to fill that empty space, and I find myself engaging in them in similar ways. The issue with this is that these digital platforms, as much as we try to paint them otherwise, are machines. They are machines created by corporations to mostly capture human attention, and sell ads, with sociability as an added bonus. But the main issue for me is that these platforms only really believe in one thing: growing, endlessly. More is always better: more clicks, more likes, more follows. This is also the reason why corporations exist; to make profit, to accumulate more, to expand everywhere. This is also the ultimate hunger of empire: to gobble up the world, to see the hoarding of power and its proliferation as the ultimate moral good. More. More. More.

I wish I could say that I was stronger than an empire, or a corporation, or even a silly little app, but I’m not. Each time I jump into the machine, I can feel it slowly changing my brain. Oh, I love books and reading! ‘You must read everything that is being posted, and have sharp critiques about everything happening, or else you will be irrelevant’. Writing, the great productive love of my life, the endless wellspring of joy! ‘It must spread, that is why it exists. Words are not a gift but a contagion. Turn yourself into a persona, a brand, and modulate all aspects of yourself so that the words travel further. The value in the work comes from the data: the likes, the digits. This is a thing you must do. If you don’t, then you will be a failure.’ Sir yes sir! I try to be good. I follow the rules. A schedule. A routine. I follow the numbers. The numbers go up and I am good. The numbers go down and I am bad.

I’m reminded of a character in Mary Gaitskill’s Veronica. The character is a writer, excitedly promoting her book. “She blooms out of the radio like a balloon with a face on it, smiling, wanting you to like her, vibrating with things to say.” That’s me, smiling, won’t you look at me? I am so happy, just look at my smile. I’m filled with hot air. Yes, I’m mostly deflated, because I’m lousy at this whole schtick, but still I’m here. Won’t you read me? All I ever wanted to do was sit in a chair, and read, and write little things that left a record of a life, and feel changed in small ways by words. But somehow, I’m doing this. At least I’m floating, like a balloon! But I am never even that: I’m tossing myself upwards, at a vessel that doesn’t possibly exist, and then I fall back down to the world. There I am now, a puddle. Still smiling, though.

⁂ :)

Walden, by Thoreau, is essentially the holy text of this newsletter. It gave this newsletter its first name, and then its current one, and it’s the book I revisit the most when I’m feeling lost. When I tried rereading it this month, something felt off. I was skimming the words, roaring across the pages like a tractor turning up the soil. It felt transactional, like I was trying to drag something out of the book. In a way, that completely destroys the purpose of Walden, and the thought of destroying a holy book deflated me completely. Here I am, back on Earth.

Thoreau shares an anecdote about a man wandering through a sleepy New England town, trying to sell baskets he has weaved. When the villagers decline, the weaver is distraught. Why won’t anyone buy the baskets he worked so hard on! It’s not fair! Thoreau jumps in and says, well, the issue is that he hasn’t discovered what makes a basket worth buying! The problem is not that the weaver is trying to sell his work; it’s that the weaver believes the point of creating the work is in selling it. Thoreau writes,

“I too had woven a kind of basket of a delicate texture, but I had not made it worth any one’s while to buy them… instead of studying how to make it worth men’s while to buy my baskets, I studied rather how to avoid the necessity of selling them. The life which men praise and regard as successful is but one kind. Why should we exaggerate any one kind at the expense of the others?”

When living the wrong life I feel like that basket weaver, obsessing over why it is that success has not effortlessly floated to me. But when I’m closer to my right life, there isn’t any room for wishing for success: I’m too busy working, and living, and enjoying not only the reading and the writing but the good life outside of it. All I can do is try to make good, study work that some people might enjoy, but even then I have to work with the expectation that all of the letters and life’s work will end up in a box, like Hirayama’s pictures. It would be wonderful if people thumbed through the box and took from it what they want. But I only have miniscule degrees of control over that process. All I can focus on is the basket, and the weaving, and then setting it down on the river and allowing the water to take it.

The loneliness of the weaving and art making is hard to swallow. One of my favorite subgenres of book, or interview, is anything about a writer’s routine. Occasionally you get fun quirks from these, like how John Steinbeck meticulously sharpened exactly 24 Blackwing pencils before writing, or how Balzac supposedly drank 50 cups of coffee a day. But mostly the routines are dull, repetitive, and incredibly lonely. Philip Roth supposedly woke up, wrote in his shed until 6 p.m., watched the news on TV, and then slept. Exhilarating! Stephen King famously instructs writers to place their desk in front of a blank wall. What a view! But we have The Shining and Sabbath’s Theater to thank for this austerity. Perhaps the dullness was worth it.

⁂

Even though Perfect Days is a lovely, charming film, it’s also tinged with sadness, as I mentioned. Hirayama’s life seems to be missing a crucial thing: people. The times that he does interact with others feel explosive, and drenched with meaning, because they’re so rare. He’s nourished by that love, but he also needs the solitude. It is the only way that he knows how to live. It is the only way to continue the discipline. He believes in living a simple and quiet life, stripped down to its essential facts, but he is also a lone person living a life that his world doesn’t see as inherently valuable. All that most can see are the absences and the missing things. Because of this, Hirayama will always be vaguely adrift, never quite fitting in with the world. But still he replants his saplings, and takes his photographs, and keeps himself open to the possibility of being transformed by the world. It’s the tension of a life’s work committed to making art, yet still trying to be with others. The balancing act is never perfect. But he tries. That’s what matters.

The film ends with him driving through Tokyo. The sun peeks in and out behind the long blocks of buildings. Shadows drape over the windshield. On the stereo he plays, oddly enough, Nina Simone. She is a singer that seems far in all ways from the surface perceptions of what a man like Hirayama should be. But still he is open to the music. He is never closed off to the revelation of life and art. And when we look at him last, he’s crying. Smiling, but crying. The joy and the sorrow held together. Sorrowful, yet rejoicing. It is not the perfect life, or the ideal life, or possibly even the right life. But it’s a noble attempt. He has found his vessel.

Brilliant again. More more more, as you say. And I am weary of the same things.

I hadn't managed to read books with any consistency for a long while now and then in July I read one book that seemed to open the floodgates for me to go back to book reading, and now I am ravenous. Of course, the reading of books all the time has meant less time on my phone, reading Substack posts, which means (I think) less of me engaging with other writing, which means less of people engaging back, and that of course scratches the opposite side of the more more more itch you described so well. Sitting with that feeling has been uncomfortable but instructional. Do I want to go back to only reading posts online, because then some of those people will read my work and I will see those damn metrics go up (likes and shares and subscribes, oh my!) or do I want to read the long reads, the books, the slow, quiet stuff that takes days and weeks and sometimes months to finish, even if it's happening like a tree falls in the forest that no one hears?

the answer is that I want to do more of the second, and then read what I'm really drawn to read here, and if that means my numbers tick upward more slowly, or even tick downward, that's ok. I like it in the deep.

(I do of course have to caveat all this with the fact that I couldn't read at all two years ago. My brain had just about melted, and the only thing I could get through were online posts or articles. I think regular reading of Substack posts was a huge step in exercising my brain enough that it could handle books again).

This was wonderful. Tell me why your last line nearly made me cry?! I loved all these thoughts and the way you linked them. The thoughts of right life/wrong life resonate so much. We have discussed this briefly on notes once - but nothing screams wrong life than long term illness, and completely encourages an existential crisis of this is not the right life for me. But ultimately, over lots of time and therapy, I had to learn how to see bits of good and allow right & wrong life to merge together into just life. That is not to say I don’t panic often about the trajectory of my life that I have pretty minimal control over. Having to change my dreams & goals is a whole other aspect that I haven’t been able to come to terms with yet. Sometimes being in denial feels like you can trick your brain into ‘we will get to the right life soon’.

I must watch Perfect Days now! Thanks for this essay, it was so good!!