The dust is not forever

War, Palestine, the struggles of moving, trying to find hope, and 'The Grapes of Wrath'

Each time that I move I decide that I will never, ever, move again. The future will find me settled in my forever-home, in a little apartment where I can drill shelves into the drywall and let the plants vine along the ledges. There will be a cat. I will know my neighbors. I’ll be able to go to a café long enough that the barista will know my order, and we’ll talk about the weather and the basketball team, and maybe then living month to month in a big city will feel worth it. But it never seems to work out. September was full of cardboard boxes, packing tape, and bundling glass and fragile mugs into bubble wrap and old t-shirts. Twelve moves in twelve years. What for? I truly don’t know anymore.

You’d think that I would have a system to handle packing logistics by now. But I don’t. I gathered the boxes weeks ahead in early September, hammered out the moving details, and bought a storage unit, but still the last days of the move were chaotic and panicked. Suddenly it was nearly the final hours, 3:41 am. There was a bottle of rum that I absolutely could not take with me, so the only thing to do was drink it as I threw papers, clothes, and broken art into a garbage bag. I sat in an empty, cavernous blank room that used to be my bedroom. Phoebe Bridgers and John Prine echoed along the walls. Perfect acoustics. Some of the papers were drafts and letters and Christmas cards from dead people, probably, but I didn’t have time to check anymore. Drinking, quickly. A flight in hours. Warm and swaddled by rum, but frightened. Dust bunnies on the hardwood floors, dust around the outlines of where a life used to be, dust on my hands. Not even thinking anymore. Just moving.

⁂

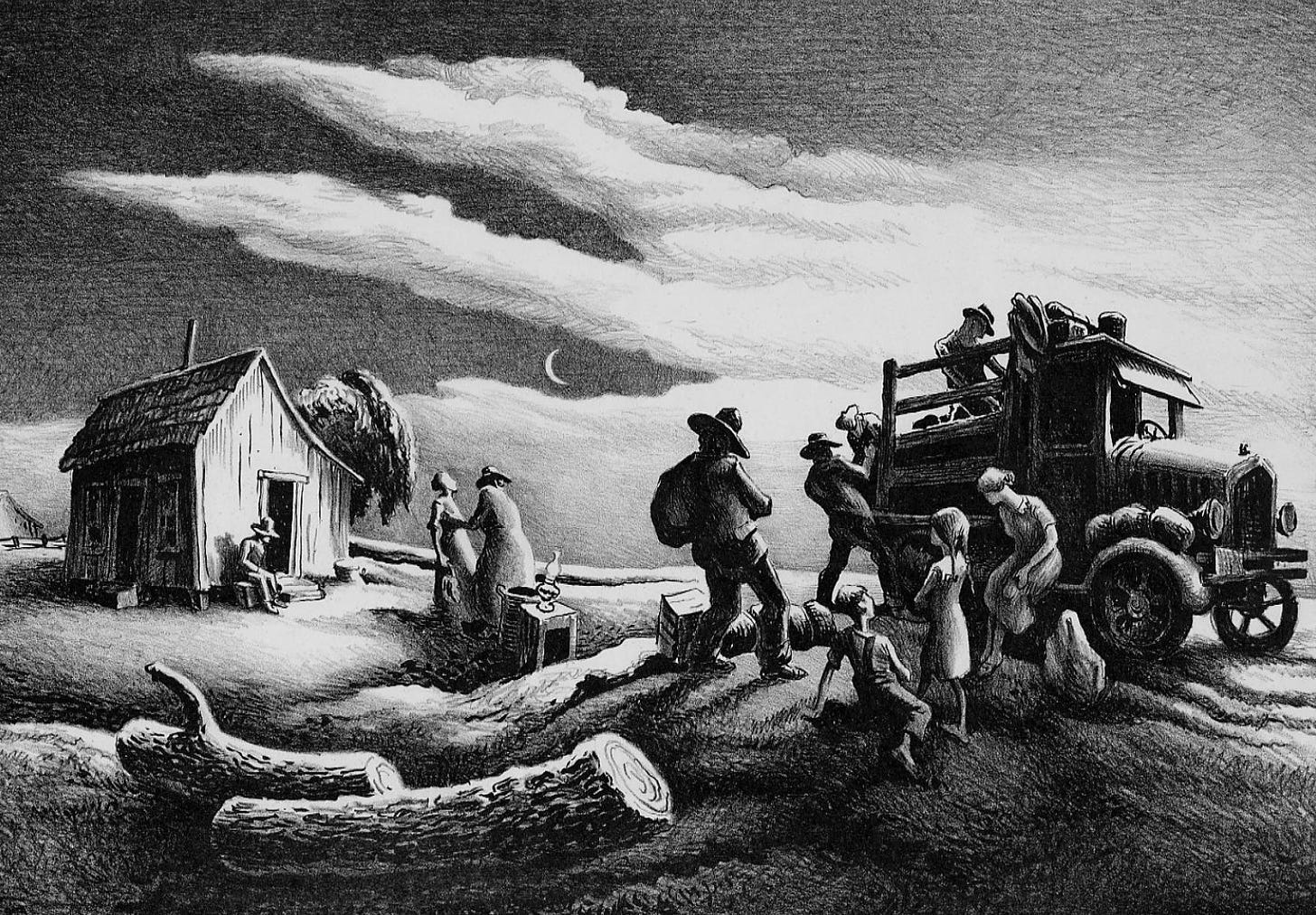

When the packing and moving is at its worst, I think of the Joads from The Grapes of Wrath. In Steinbeck’s novel the Joads are farmers preparing to leave home in the wake of a great catastrophe. The Earth has dried up; windstorms thousands of miles wide have gathered up the soil and sprinkled it over the crops, the tractors, and the children playing in the yard. The Joads are fleeing for their lives, along with thousands of others migrating across the American Midwest, and in a frantic few hours they begin to pack up their whole lives for the long trek to California. The family works as a unit, everyone assigned to a task. Pa’ prepares the Hudson Sedan to carry a crew of a dozen-plus people. Rose of Sharon gathers the clothes and levels the mattress on the truck bed. The preacher Jim Casy cleans the slaughtered pig and salts it in kegs for a week of meals. The kids Ruthie and Winfield bicker playfully out in the yard. Grandma sleeps. Grandpa sits and mulls over his dream of grabbing a whole bunch of California grapes and letting the juice run down his chin. And then there’s Ma’ Joad.

Ma’ is a character that I love so dearly that I consider her a patron saint of this newsletter. She is the moral compass of the whole family. In the last few moments of the move, Ma’ wanders through the empty house, making sure that nothing important was left behind. She flips through an old box in the corner, full of clippings, letters, pictures, earrings, a gold ring. “For a long time she held the box, looking over it, and her fingers disturbed the letters and then lined them up again. She bit her lower lip, thinking, remembering. And at last she made up her mind.”

She knows that she can’t save much of anything. Any extra weight will strain the truck, and a breakdown could be a death sentence. The family only has $150 dollars to their name, even after selling everything. So she slips a letter into an envelope, along with the earrings, the ring, the watch charm made of braided hair. And then she closes the box, carries it to the kitchen, and lays it among the coals in the stove, and watches as the flames overtake the letters and the pictures. Destruction is the only way to ensure the family’s survival, Ma’ decides.

⁂

September has reminded me how small a life can appear. A few boxes packed in a truck. Garbage bags. A wrapped mattress. Dust left behind. It reminds me of what Carl Sagan said of our planet, looking at a picture of Earth taken from Voyager 1, 3.7 billion miles away; “A mote of dust, suspended in a sunbeam.” Here I am, an even more microscopic particle on that larger mote of dust, and to me the slightest wind is a maelstrom. A cross-country move. A breakup. Saying farewell to people for possibly forever. These things absolutely wreck me. I get sad over my last coffee at the neighborhood café. I’m distraught in the middle of an empty room. But then I think of the Joads, and I’m a little more grounded in my small tragedies. Unlike me, the Joads don’t really choose to leave. They’re forcibly uprooted. Climate catastrophe has made the land they love unworkable. Banks and corporations sweep in from the east, buying up the cheap land of the tenant farmers and turning the small family farms into monocrop factories, and terror follows in their wake.

A distinct image of the terror of the displacement is of tractors hired by the banks churning through the fields, barreling towards homes. Some of the farmers threaten to fight back. The drivers of the tractors reply that they don’t make the rules, they’re just following orders, if you have an issue take it up with bank. The farmers say, well, there must be someone that I can fight with, someone that is responsible. And the tractor drivers say no, there’s really no one, not even the head of the bank is truly responsible, because what’s really in charge is the machine. People can drive the tractors and wield the clubs that bash protestors and dissenters, but at a certain point the force of the injustice is so cold and cruel that it can only be seen as nonhuman. People can’t believe that such injustice could be done by other humans. And then the tractors churn forward and bulldoze the homes. They raze the gardens, fill the wells, destroy the windmills and the barns and all the things that are made by the hands of people who love and care. The whole land is flattened. Thousands of acres of monocrops are planted in the dying soil. The corporations pump the earth with chemicals. The birds and the bees die, but some corn grows after many years, so the corporations tell everyone that they’ve found a desert and turned it into a garden.

People like the Joads flee in the wake of their lives being destroyed. They drive out west, the dust kicking up behind their trucks. As migrants they are ridiculed, belittled, blamed for the minuscule blame they share in a massive historical tragedy. I’ve been thinking about the Joads when it comes to the victims of Hurricane Helene. Hundreds killed, hundreds of thousands displaced and torn away from their homes. The massive storm is almost godlike in its terror and scope, but it is fueled by human destruction of the climate. A loud and ever-present group of people jump in to ask the victims ‘well, why didn’t you just leave’, or ‘well that’s what you get for voting for the wrong party’, and they say these things while the victims look at the splattered wreckage of their homes, or while they frantically call around to see if they can hear anything about a missing person. There are so many Joads across Asheville and the American southeast and Appalachia. There will likely be more in the aftermath of Hurricane Milton.

And the Joads this year have been in Gaza, in the occupied West Bank, and in Lebanon. They have been in Palestine for far longer than a year. 41,000 people killed in Gaza, likely far more buried and unrecoverable. Thousands killed in Lebanon in the past few weeks. In Gaza, 17,000 children are now orphaned. More than half of the Gaza Strip’s homes are damaged or destroyed. 87% of schools. 68% of the cropland. Farmland coated with American bomb-dust. Hospitals, mosques, gardens, whole city blocks shredded by bombs sent by the United States. 1.9 million people have been internally displaced in Gaza. 90% of the population. A whole people forced to flee their homes, hopping from camp to camp, following evacuation orders that lead them nowhere. Children dying from starvation. Outbreaks of polio.

Two nights ago I read the story of Hassan Hamad, a Palestinian journalist covering the massacre in Gaza. Some days ago, he was threatened by Israeli officers over the phone. They told him to halt his reporting. Or else. When Hamad refused, Israeli airstrikes arrived and leveled his home in Gaza’s Jabalia refugee camp. He was instantly killed. Pictures later circulated of his colleagues carrying small plastic bags containing a shoebox. It was his body. That is it, a human life. A human being can fit in a shoebox.

A click away from Hassan Hamad’s story was a thread of photographs taken by the journalist Sally Hayden. She had gone through fields of rubble in Lebanon with her camera, capturing the things left behind in the wreckage of apartment buildings. A stuffed giraffe, playing cards, photographs of hugging families, clothes, pink slippers, puzzle pieces, university homework, rugs, books, sofas, teddy bears. It is like the people have simply vanished. In all of these pictures there is dust on the roads, clouds of dust in the wake of trucks and motorcycles, dust on the abandoned objects, dust on the children being carried on stretchers.

Even before this massacre began, there was an infamous symbol of the generations-long attempted erasure of the Palestinian people. It is of tractors plowing into homes, tearing out olive groves, filling wells, pushing the people further away from the homes and the villages that they had worked and known all their lives. The people took what they could and fled. Many held onto the keys for their houses, hoping that one day they could return. And sometimes they did return. They walked to the border, peacefully, and were shot by snipers. And then others decided to act differently.

John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath noted that such a thing could happen. After watching their homes razed and families threatened, maybe some people would decide to pick up the old hunting rifle from the mantle. It’s a possibility. Similar things have happened for tens of thousands of years. What happens when the dream of something so simple as home is repeatedly denied? Langston Hughes famously asked the same question in his poem, Harlem,

“What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?”

⁂

When the war started a year ago, I wrote a letter on October 10th that I somewhat still agree with, but largely don’t. I mostly stand by the core things I say in the middle and end of the letter; “America is still the global hegemon, and the country responsible for the entire world order, but the world order specifically that allows this crisis in Israel and Palestine to persist. They supply the guns and missiles that will be dropped on Gaza. This next massacre will be enabled, and abetted, by the United States.” Yes, this is an American war and an American massacre, and it doesn’t have to be this way either.

But I no longer agree with most of the piece, especially the beginning. I talk about how I’m against war, how I believe that violence begets violence, and then I top it off with the Gospel of Matthew. I think there’s validity in these viewpoints, but what bothers me now is the preachiness of the tone. It’s not religiosity I’m fearful of; it’s any kind of tone where the author elevates themselves far above everyone else. This has become a popular tone for writers and pundits who want to commentate on the war without picking ‘sides’, or making decisions at all. It’s a tone that The Grapes of Wrath is especially concerned with.

One of the first characters that pops up in the novel is Jim Casy, a reverend who has strayed from the faith. Casy is far from his days of making parishioners shake in the pews and speak in tongues; he’s watched the houses being leveled, and the people in flight, and now he’s solemn and apprehensive, circular in the ways he talks. He tells Tom Joad about what he would preach now, if given the chance.

“Why do we got to hang it on God or Jesus… maybe it’s all men and all women we love; maybe that’s the Holy Spirit – the human spirit… maybe all men got one big soul and everybody’s a part of it…”, and Tom says rightly that he couldn’t hold any church with ideas like that, and he’d be run out of the country too. And later on, when the Joads are about to leave, they ask if Casy will return to the preaching in California.

“I ain’t gonna baptize. I’m gonna work in the fields, in the green fields, and I’m gonna be near to folks. I ain’t gonna try to teach ‘em nothin’. I’m gonna try to learn… Gonna hear ‘em sing… Gonna lay in the grass, open and honest with anybody that will have me. Gonna cuss and swear and hear the poetry of folks talking. All that’s holy, all that’s what I didn’t understand. All them things is the good things.”

The Grapes of Wrath believes the answer is somehow in those things. “The people in flight from the terror behind – strange things happen to them, some bitterly cruel and some so beautiful that the faith is refired forever.” The terror within the novel is harsh and real, but under the dust is the other world. Compassion, comradery, solidarity, networks of people banded together, people asking ‘what is to be done?’ and then immediately getting to work and building it. Things that can exist now, and already do. Networks of support. A warm meal. A simple pay-it-forward coffee.

Last night, while writing this, I went to a local café for chai. It is Palestinian owned, and it was October 7th. The room was full of people chatting, smiling, tying flags to poles, preparing signs. The shelves were full of books, for everyone. Pamphlets and resources were laid out for people seeking help. While I was there a man walked loudly through the door. He was shaking, desperately thirsty. One of the patrons stood up and asked, ‘water?’, and when the man nodded yes the patron pointed him to the jug of water and helped him get it. No one judged the man, no one told him to leave. He sat quietly on a bench and looked around the room. And when he was done with his water he stepped out of the café, and the other patron from earlier followed. My momentary cynicism thought there might be a confrontation, a warning, a ‘don’t come back’. But, no, the patron wanted to stop and chat. It was to say hi. It was to make sure he was okay. They walked off into the night together. Steinbeck said this of Ma’ seeing her son Tom, after months of worrying that she might never see him again. “And her joy was nearly like sorrow.” Sorrowful, joyful, some dust finally lifting.

it’s strange, kind of, with how present the grapes of wrath is in like the high school literature canon that I don’t really hear people talk about it, mention it and point to it and its message as much as say—the great gatsby or catcher in the rye. We watched the film in the my hs American lit class and it changed my life. Every single one of my classmates fell asleep and I could not look away. The film still lives in me to this day. Everyone needs to be talking about the grapes of wrath, everyone needs to think about the grapes of wrath, everyone needs to think about Tom Joad and Jim Casy. You think we are so far removed from the time period of this book? All of this happened less than a hundred years ago. This time span is nothing, it is a drop in the bucket of human history. I don’t know what else to say, I will take every opportunity to get on a soapbox whenever anyone mentions the grapes of wrath

beautiful piece, i just watched the grapes of wrath movie and this really resonates. thanks for sharing, and good luck on your move